Spoiler alert: plenty spoilers for Deep Carbon Observatory. I accidentally revealed some of these to a friend whose DM had been building up to running DCO with them for 18 months. Oops!

Patrick Stuart’s Deep Carbon Observatory (DCO) is a piece of writing so captivating, so strange. Beyond hobby, becoming art. It drew me into “the OSR” and, for the first time since the 1980s, made me really, really want to run a game.

DCO is set in valley in the wake of a dam burst. The opening scenes, of refugees and ruin, are apocalyptic and fast-paced. But the valley has an ancient history, aspects of which are slowly revealed as the characters adventure onwards.

A charge sometimes levelled against DCO (by idiots with no imagination) is that the book contains too much backstory – information “for the DM’s eyes only”. Knowing the 5,000-year backstory to the scenario certainly spices up the DMing of DCO, just as a bay leaf spices stew, but there are also plenty of opportunities to allow the players more direct access to the deeper history of the valley (several of the adventure hooks begin this process).

Perhaps the easiest, most fun way of doing this is running the adventure using the Weird North (WN) rules. Like Electric Bastionland, Cairn, Mausritter and others, WN is based on Into The Odd (ItO), and is set in a grimdark world where characters have divinatory and prophetic powers. It’s the perfect partner for DCO.

WN shares most of its mechanics with ItO, but it adds two things. Archetypes (character classes) and Corruption. Both are a lot of fun, and both add mechanics whereby players can access historical information.

Some of the archetypes map more-or-less onto D&D character class, although all have access to some specific and often unusual abilities and restrictions, so a Contender (basically a fighter) might gain a strength bonus in front of a large audience, a Sepulchrite (thief) might be unable to resist stealing any religious relic, and a Warden (ranger) might improve their abilities by restoring order to chaos.

But the three other archetypes are more unusual, and scrape beneath the skin of the dam-builders’ ancient history.

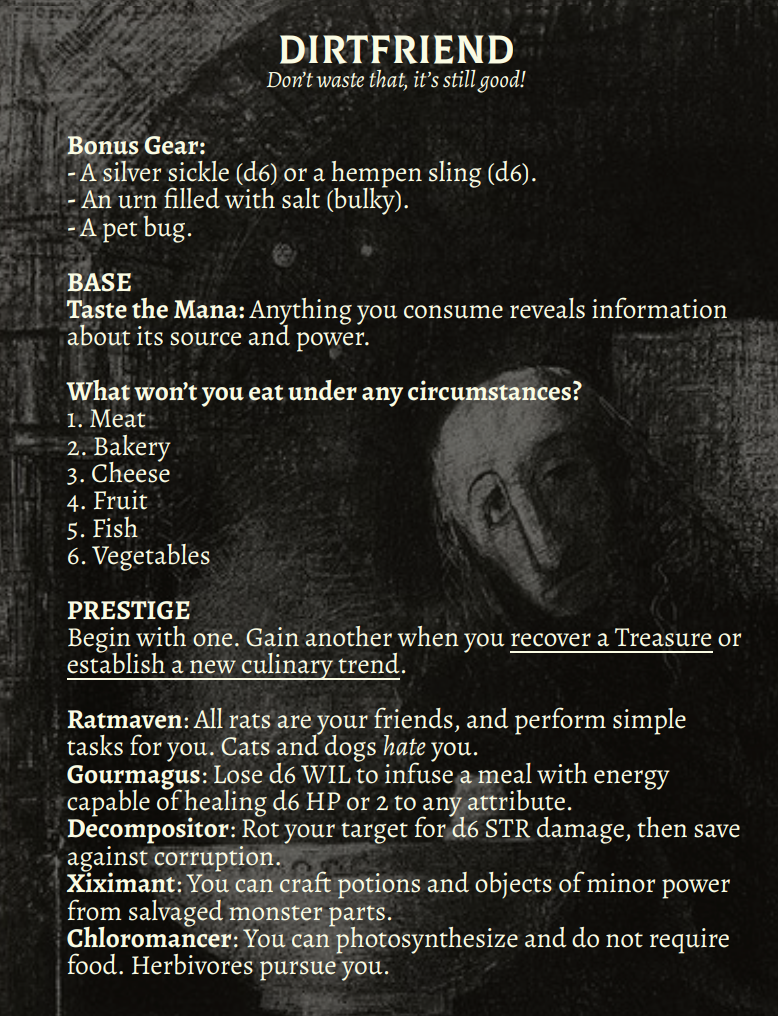

First, meet the Dirtfriend:

You see a stone sarcophagus floating downriver. Inside is a mummy with a mask made of lapis lazuli and gold. In its left hand is a Branching Key with teeth arrayed like silver leaves. In its right hand, an iron sword.

I pull a bit of bandage from the mummy’s face and suck on it.

The bandage disintegrates on your tongue. It tastes of ancient civilisations. It leaves a gritty, peppery burn at the back of your throat.

I lick the branching key.

A cloying mist dissipates. A stone room. Murals. A pillar decked in chains.

I lick the sword

Bitter metal , blood and earth. The sword seeks fear. It holds deep, deep sorrow, felt only by the dead.

Ironically, our party’s dirtfriend could not bear to eat fish, the one food that the valley has in abundance.

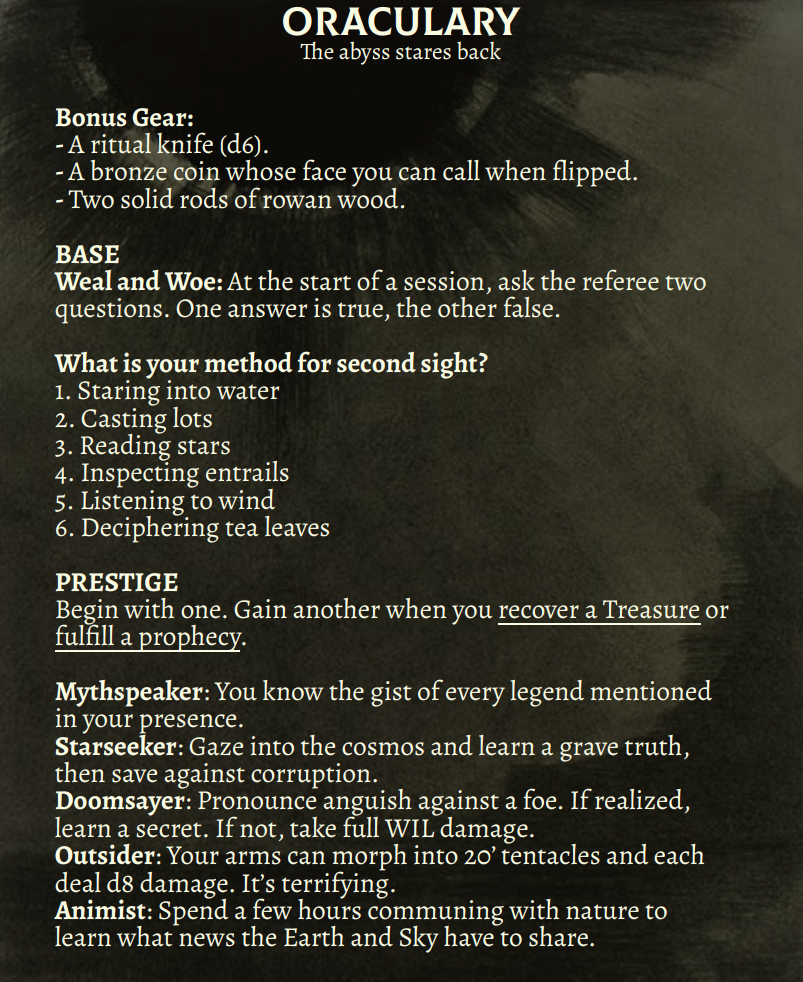

Next the Oraculary:

I whisper into the wind the questions “Weal and woe, who peers through my extra pupil?” and then “Woe and weal, how will we safely take the treasure in the lake?”

The wind whispers back “Weal woe, Ghar, Ghar, Ghar, Ghar” and “Woe weal, you needs be good swimmer. Such good swimmer.”

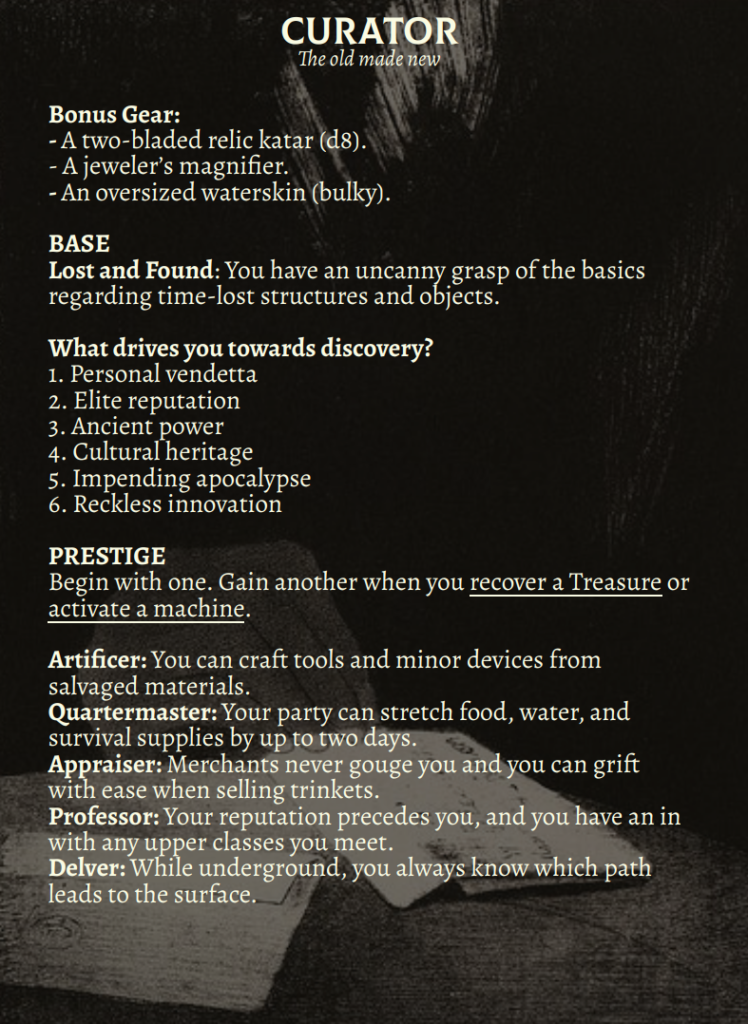

Finally, the Curator:

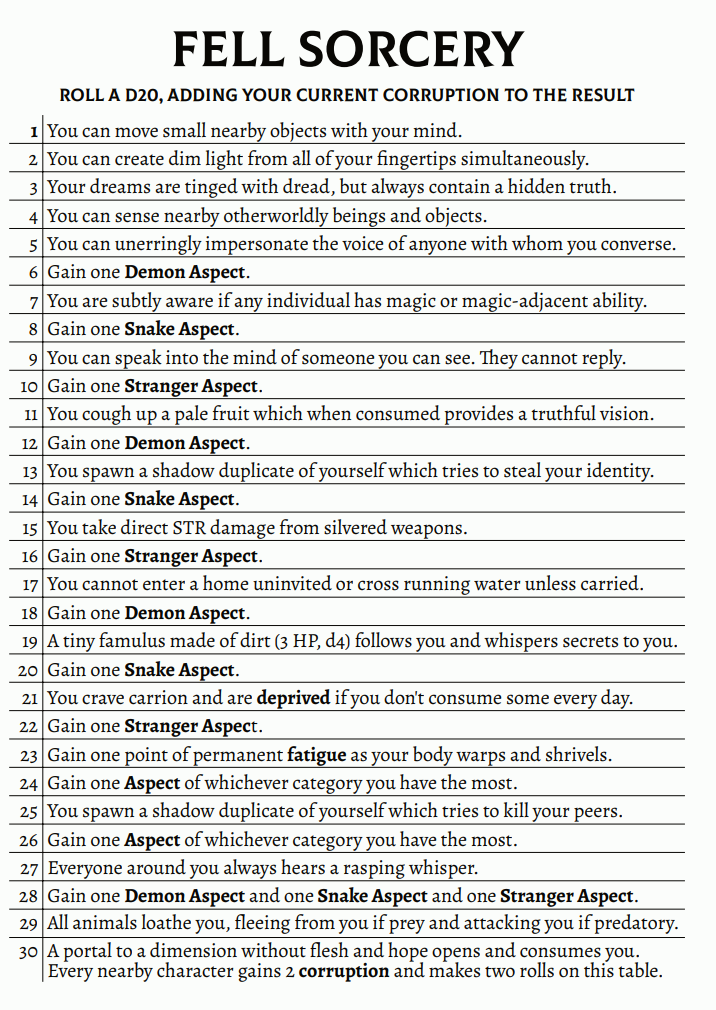

The game also has a mechanic for corruption. Every horrific experience adds a point of corruption. With each point, the character risks gaining small (though often useful) mutations and curses. As they build, the character becomes more powerful but also loses control, until finally they are sucked into another dimension and out of the game.

Corruption points should be handed out liberally. At some point in the campaign, characters should start popping out of existence.

And that’s pretty much it as far as mechanics goes – the rest of the game’s rules are identical to Into The Odd’s.

I’ve run DCO twice using WN rules. Each game has been brilliant: creative and engaging. There’ll be a play report from one of these games in my next post.

Leave a Reply